Between 2009 and 2013, I examined Inuit and non-Inuit sod houses in southeastern Labrador from Pinware to Red Bay, St. Lewis Inlet, St. Michael’s Bay, and in the Frenchman’s Island/Seal Island area. One site along the Quebec North Shore was also tested. Using both archaeological and archival data, the focus of this study was the nature and timing of the most southerly Inuit settlement in eastern Canada. Also of interest were the multi-faceted nature of Inuit relations with Europeans, and the material culture of the contact zone. From the outset, it was clear that Inuit settlement in the studied areas dated to at least the early 1500s, and that a range of material goods represented contact with first the Basques (minimal evidence), then with the French (much evidence), and after 1763 with the English (much evidence).

This web page presents some of the research results of the excavation that took place in St. Michael’s Bay. As analyses proceed, more results from the 2009-2013 fieldwork will be posted. The links at the top of this page are to data sets from the St. Michael’s Bay site such as ceramic wares, artifacts relating to clothing ornamentation, bone artifacts, and the results of analyses of faunal remains, mussel shells, and soils/entomology. In way of making this material available, below are links to publications related to the 2009-2013 work and to my overall work on the prehistory and history of Labrador and the Northeast. Topics include hunter-gatherer mobility, food storage, Inuit, Innu, as well as historical figures such as Mikak, Caubvick, Tuglavina, Attuiock, Ickongoque, Lydia Campbell, and Captain George Cartwright. Other work includes a study of previously unknown 18th century Labrador Inuttitut (Inuktitut) word list, and a history of Chateau Bay that includes a new 18th century map of that bay.

The overall project (http://www.mun.ca/labmetis/) was funded by a federal SSHRC-CURA grant that covered field and research expenses and student training, and was administered through Memorial University of Newfoundland. Summer student grants from NunatuKavut (formerly the Inuit Métis Nation) brought aboard local students, while Northern Scientific Training Program grants covered some of the costs for students from Memorial Univ. and from the Univ. of New Brunswick. All analysis, writing, and public presentations are completed as part of my volunteer commitment to southern Labrador.

What should you do if you think you’ve found an archaeological site in Newfoundland and Labrador, or an artifact of stone, bone, ceramic, or anything else that seems “old”? Contact the Provincial Archaeology Office at (709) 729-2462 (http://www.tcr.gov.nl.ca/tcr/pao/ / e:mail is pao@mail.gov.nl.ca). Labrador has a rich archaeological heritage that is important for understanding the history of its people, and it is also an important part of the history of Canada. Archaeological material in the province is protected under the Historic Resources Act. Only a qualified archaeologist working with a permit can excavate and collect archaeological material. Removing artifacts from the ground will destroy all meaning and historical value – show care for the past by saving it for an archaeologist.

All site and artifact photos are part of ongoing research and not for use without permission.

![]()

THE FIELDWORK

I completed the first archaeological survey of St. Michael’s Bay in 1992, and further survey in 2010 and 2011. Surprisingly few sites were found relative to the bay’s size and its more than 300 islands. Since 2009, research has focussed on the early Labrador Inuit occupation of this region. The site of North Island-1 is an undisturbed Inuit site with two sod houses, each associated with mussel shell middens. A suite of radiocarbon dates as well as cultural material give a date range from the late 15th century to the mid 18th century.

As long ago as 1992, it was clear that this site was unique. Ceramics showed it to be early in the Inuit settlement timeline for southern Labrador but also revealed a second unique factor, namely that Inuit had trade ties with the French. French fisheries began on this coast in the early1500s alongside Portuguese vessels, Spanish, Basque, Dutch, and English. Of all these groups, the French maintained the most persistent presence, still fishing Newfoundland’s French Shore in the twentieth century. There were many opportunities for contact between Inuit and French: crews had land-based operations set up along both shores of the Strait of Belle Isle, and a series of French merchants held concessions of the southern Labrador coast from the mid-1600s until 1763. Many historic documents show that Inuit acquisition of European material culture was both through trade and through pillaging of shore-based fishing stations. Ceramics recovered at North Island-1 hint at contact with Portuguese and show definite contact with French. The early historic settlement of Inuit presence in southern Labrador is part of my project’s research scope. Of particular interest is the search for the missing links between early Inuit and early Euro-settlement. Where do the two come together, and why? The results of my ongoing research are found in the links and publications listed below.

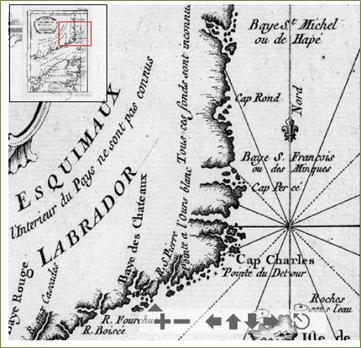

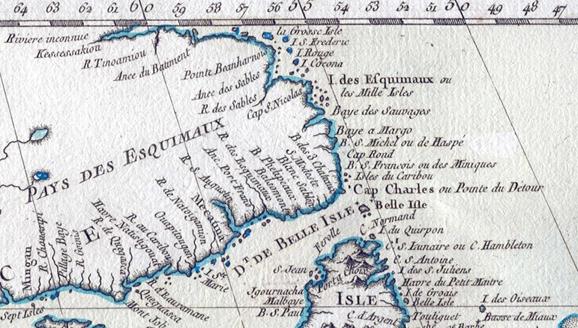

French knowledge of the St. Michael’s Bay area is evident in these 1764 maps published by Jacques-Nicolas Bellin (1702-1774). St. Michael’s Bay was at that time known to the French as “Baye St. Michel,” but also, “Baye de Hapé” or “Baye de Haspé.”

(Source: J.-N. Bellin, Le petit atlas maritime, 1764, Library and Archives Canada, Mikan 382207)

![]()

Results of ongoing analyses are through links at the top of this page. The links below are:

- summaries of 2009 – 2013 fieldwork, and

- broader research on Labrador prehistory and history

![]()

FIELDWORK SUMMARIES 2009 – 2012

Summary report of the 2009 excavations of Labrador Inuit sod houses in St. Michael’s Bay

(co-authored with C. Jalbert)

Summary report of the 2010 excavations of a Labrador Inuit sod house in St. Michael’s Bay

(co-authored with K. Wolfe)

Podcast of 2010 CBC (Cornerbrook) interview: https://www.facebook.com/cbccornerbrook/posts/149445811742945

Summary report of the 2011 excavations of a Labrador Inuit sod house in St. Michael’s Bay

Summary report of the 2012 Labrador Inuit fieldwork in Seal Islands area, southern Labrador

FURTHER RESEARCH ON LABRADOR HISTORY AND ARCHAEOLOGY BY M. STOPP

George Cartwright’s The Labrador Companion

Published in 2016, this volume presents a newly-discovered Canadian historical document. Written in 1810 by Captain George Cartwright (1739-1819), it is an instructional record of the everyday work of a Labrador merchant involved in Britain’s fur trade empire as it was conducted in the northeastern corner of the continent. It also contains one of Canada’s earliest natural history records based on first-hand observation. Available in cloth, paperback, or eBook at: http://www.mqup.ca/george-cartwright—s-the-labrador-companion-products-9780773548060.php?page_id=105621&#!prettyPhoto

The New Labrador Papers of Captain George Cartwright

Published in 2008, this volume presents previously unknown writings of Cartwright that complement his 1792 journal of daily life in southern Labrador. The New Labrador Papers contains a manuscript entitled Additions to the Labrador Companion, also an essay-length text about Labrador, correspondence, and lists of things to bring to Labrador. It is a unique insight into 18th century methods and material culture related to a northern frontier establishment (how to build a house in a sub-arctic climate, how to set all kinds of traps, how to catch seals, and salmon fishing), as well an understanding of merchant rivalries and trade with Aboriginal groups. Available in cloth, paperback, or eBook at: http://www.mqup.ca/new-labrador-papers-of-captain-george-cartwright–the-products-9780773533820.php#!prettyPhoto

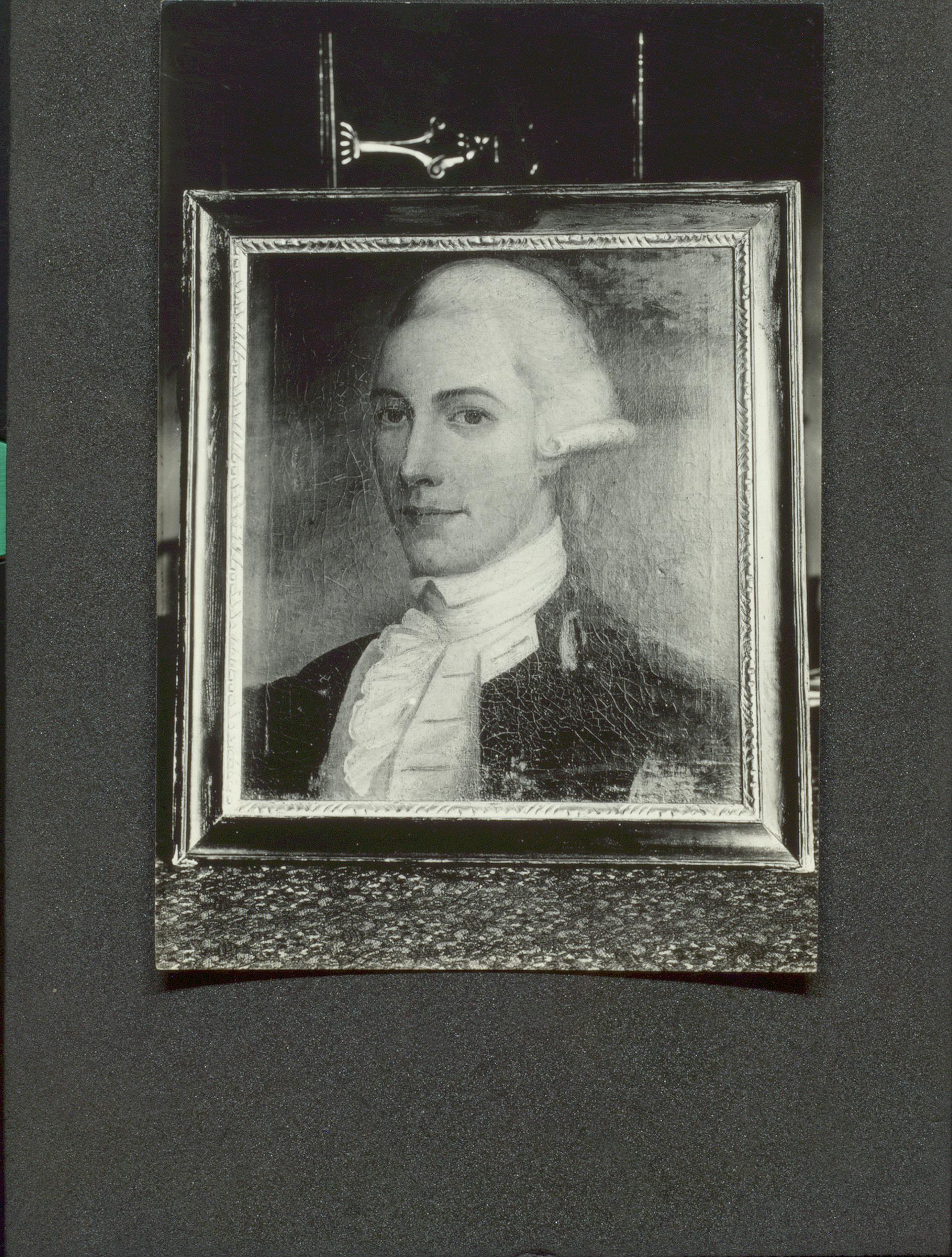

The original oil painting of George Cartwright discovered in South Africa by Dr. Ingeborg Marshall. Now in collection of Library and Archives Canada.

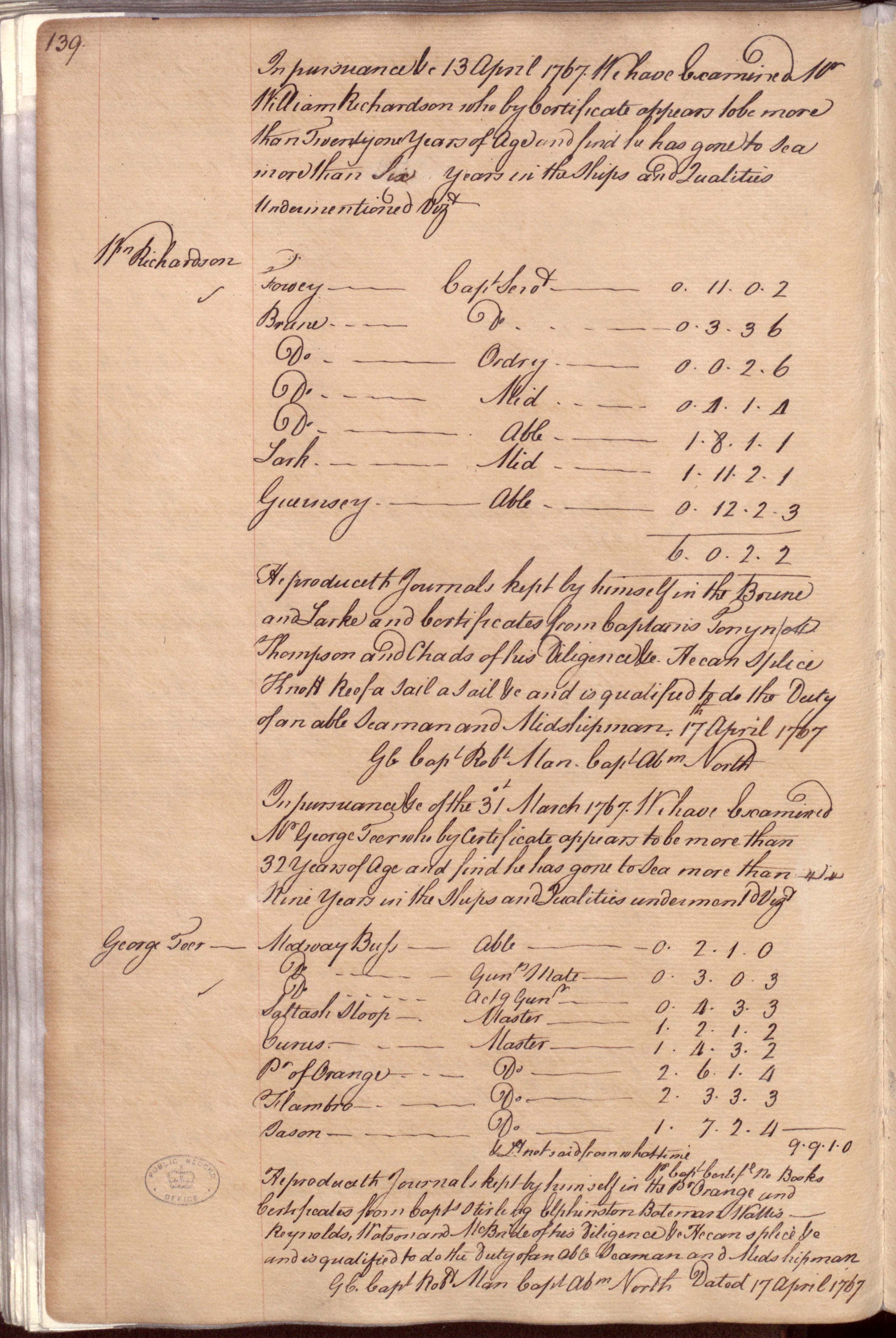

William Richardson (b. ca. 1746 – d. 20 July 1772) and southern Labrador

Chateau Bay, Labrador, and William Richardson’s 1769 Sketch of York Fort.pdf (2014. Newfoundland and Labrador Studies 29(2):244-271) [Paper available through Newfoundland and Labrador Studies]

A newly discovered image of York Fort, Chateau Bay, and a rarely seen 1766 map of Chateau Bay. William Richardson (below) is known to researchers of Labrador history for his account of a 1771 voyage along the coast of southern Labrador. In a re-examination of the William Richardson material at the University of Toronto Libraries, an unexpected discovery was a sketch of the British palisaded blockhouse known as York Fort (1766-1775), drawn by Richardson during a voyage to Labrador in 1769. This paper has three objectives: to present and describe Richardson’s sketch; to provide historical and archaeological information about York Fort; and to present an overview of the human history of Chateau Bay.

The origin of William Richardson’s 1771 Description of a Labrador Inuit Snow House.pdf (2013). Etudes/Inuit/Studies 37(1):95-102)

The complete Labrador Inuttitut vocabulary collected by William Richardson ca. 1765-1771.pdf (2014). Regional Language Studies…Newfoundland. 25:1-22)

- William Richardson’s Lieutenant’s Passing Certificate of 17 April 1767 (top half of this page). (ADM 107/6, 139)

Southern Labrador + Inuit Archaeology and History

Faceted Inuit-European Contact in southern Labrador Etudes Inuit Studies 39(1):63-90).

Archaeological evidence from three sites in southernmost Labrador excavated or tested between 2009 and 2013 is shown to be valuable for interpreting the diverse nature of the early Inuit-European contact zone and helps to decolonize Inuit history. It points to a more nuanced contact landscape than suggested by the written records, with clues to varied cultural intersections, and Inuit resilience and persistence.

‘I, Old Lydia Campbell’: A Labrador Woman of National Historic Significance (2014). Lydia Campbell has been designated a person of national historic significance in Canada.

Eighteenth Century Labrador Inuit in England.pdf 2009. Arctic 62(1):45-64).

In the late eighteenth century a number of Labrador Inuit were at different times taken to England. Their lives and journeys were unusually well documented through writings and portraiture. Presented here are the histories of Mikak and her son Tutauk, brought to England by Francis Lucas in 1767, and of Attuiock, Ickongoque, Ickeuna, Tooklavinia and Caubvick, who travelled to England in 1772 with Captain George Cartwright. These individuals, especially Mikak, played a part in Britain’s expansion along the northeastern seaboard, and all were keen players in a changing economy. Although the general histories of these individuals are not unknown to students of Labrador’s past, this paper brings together new information, it includes references for the presented information, and it clarifies discrepancies in earlier publications. The portraits are particularly striking for their ethnographic content and include two newly discovered images of Labrador Inuit.

The Story of Mikak .pdf – paper prepared for Nunatsiavut Government (2007).

This paper formed the nomination application submitted to the federal government in 2007 to have Mikak considered as a person of national historical significance by the Historic Sites and Monuments Board of Canada. Mikak received the designation in 2009. Alongside Lydia Campbell, she is the second Labrador woman to be honoured in this way.

“Our Amazing Visitors”: Catherine Cartwright’s Account of Labrador Inuit in England.pdf (2010. Arctic 63(4):399-413).

(co-authored with G. Mitchell)

Following the publication of Eighteenth Century Labrador Inuit in England (Arctic, 2009), further Cartwright material was discovered in a British archive that stands as a relevant sequel. Presented here are three letters written in 1773 by Catherine Cartwright, sister of Captain George Cartwright of Labrador fame. The letters describe and discuss the group of five Inuit who came to England with the latter in the autumn of 1772.

Settling a rocky shoreline: possible Inuit structures in southern Labrador – a slide show / paper presented at 2006 conference of North Atlantic Biocultural Organisation, Quebec City.

Reconsidering Inuit presence in southern Labrador.pdf (2002. Etudes/Inuit/Studies 26(2):71-106)

This paper reconsiders the century-old question of Inuit presence south of Hamilton Inlet and the contention that it was a short-term presence for the purpose of trading with Europeans.

Long-term coastal occupancy between Cape Charles and Trunmore Bay, Labrador.pdf (1997. Arctic 50(2):119-137)

Presents the results of the 1991 and 1992 Labrador South Coastal Survey.

The archaeology of George Cartwright’s Ranger Lodge (ca. 1770), his first home in today’s Lodge Bay, Labrador.pdf – a slide show

M. Stopp’s 2010-2011 summer column “Field Notes” in The Northern Pen on matters related to Labrador archaeology and Inuit (The column often appeared amongst the obituaries of The Northern Pen, perhaps to remind us that archaeology is all about the long-ago and the long-gone.)

Lettuce & Labrador.pdf (2001). The Beaver (April-May):27-30)

Labrador Hunter-Gatherer-Fisher Societies

Across the Straits from Port au Choix: Mobility, Connection, and the Dorset of Southern Labrador.pdf (2016. Arctic 69 (Supp. 1):1-10)

FbAx-01: A Daniel Rattle Hearth in Southern Labrador (2008. Canadian Journal of Archaeology 32: 96-127)

Ethnohistoric analogues for storage as an adaptive strategy in northeastern subarctic prehistory. 2002. Journal of Anthropological Archaeology 21:301-328.

Après la capture des phoques et des caribous: une reformulation des modèles d’adaptation dans le Subarctique oriental (2000. Recherches amérindiennes au Québec XXX(2):51-62)

Cultural utility of the cobble beach formation in coastal Newfoundland and Labrador.pdf (1994. Northeast Anthropology 48:69-89)

Battle Harbour in a Time Before Memory.pdf (2013) – a slide show

Thanks to W.A. McGrath for webpage support.

Webpage Reference: M. Stopp. 2013. Inuit in Southern Labrador and the St. Michael’s Bay Archaeology Project, at, http://www.labradorcura.com/arch/.